Math 301: Homework 3

Reading:

-

If you haven’t yet, skim sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 1.6.

-

Read sections 1.7, 1.8, 2.1, and 2.4.

Exercises:

-

-

Suppose \( \binom {n}{k-1} = 210 \) and \( \binom {n+1}k = 462 \). What is \( \binom nk \)? (You can solve this without finding \(n\) and \(k\)).

We apply a property of binomial coefficients to \(\binom {n+1}{k}\) and get

\[\begin{align*} \binom{n+1}k &= \binom nk + \binom n{k-1} \\ 462 &= \binom nk + 210 \\ 252 &= \binom nk \end{align*}\] -

Show that \( \binom n2 + \binom{n+1}2 = n^2 \). (I suggest you do not use induction).

It’s pretty straightforward to show this with algebra. Here’s another way. Notice that the LHS can be rewritten \(\binom n2 + \binom n2 + \binom n1\) by expanding \(\binom {n+1}{2}\) using a property of binomial coefficients.

Now, \(n^2\) counts the number of words from the alphabet \(\{1,2,3,\cdots,n\}\) of two letters. There are three possibilities: Either the two digits in the word are distinct and sorted descending, they are distinct and sorted ascending, or they are the same digit repeated twice. Notice that the number of words with distinct digits sorted descending is \(\binom n2\), as is the number of words with distinct digits sorted ascending. The number of words with the same digit twice is simply \(\binom n1\). So, we have used combinatorics to show that \(n^2 = \binom n2 + \binom n2 + \binom n1\) which is exactly what we wanted!

-

-

How many words of \(3n\) letters from the alphabet \({a, b, c}\) have the same number of \(a\)s, \(b\)s, and \(c\)s?

We have \(3n\) letters to decide on, of which \(n\) must be an \(a\). The number of ways to decide this is \(\binom {3n}n\). We are then left with \(2n\) letters that must be filled with \(n\) \(b\)’s. There are \(\binom {2n}n \) ways to do this. We’re then left with spots that all must be \(c\)’s. Hence the number of words is

\[ \binom {3n}n \binom {2n}n \binom nn = \binom{3n}{n,n,n}.\]

-

-

How many ways can you place \(n\) rooks on an \(n \times n\) chessboard (that is, the chessboard is \(n\) squares by \(n\) squares) without any rook threatening another? (A rook threatens a piece if it lies on the same row or column).

By the way rooks attack each other, there can only be one rook per row of the chessboard. We’re placing \(n\) rooks on a board with \(n\) rows, so every row must have a rook. All that’s left to decide is which column to put each rook in, as we go row by row. There are first \(n\) possibilities, then \(n-1\), then \(n-2\), and eventually only \(1\). So the answer here is that there are \(n!\) ways to place non-attacking rooks.

Notice the answer here is \(n!\), which is the same as the number of permutations of \(n\) objects!

-

How many ways can you place \(k \ge 0\) rooks on an \(n \times n\) chessboard without any rooks threatening another?

By the way rooks attack each other, there can only be one rook per row of the chessboard. We’re placing \(k\) rooks on a board with \(n\) rows, so \(k\) rows must have a rook. There are \(\binom nk\) ways to decide this. All that’s left to decide is which column to put each rook in, as we go row by row. There are first \(n\) possibilities, then \(n-1\), then \(n-2\), and eventually only \((n-k+1)\). So the answer here is that there are \(\binom{n}{k}\frac{n!}{(n-k)!}\) ways to place non-attacking rooks.

-

-

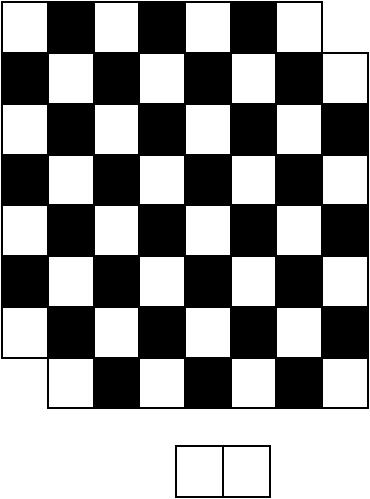

Can you cover a standard \(8 \times 8\) chessboard that has had two opposite corners removed entirely by non-overlapping \(2 \times 1\) dominoes? (You are allowed to rotate some dominoes).

By the way a chessboard is colored, every domino has to cover 1 white square and 1 black square. An \(8 \times 8\) chessboard has 64 squares, of which 32 are white and 32 are black. We remove two black squares, so we end up with a chessboard of 62 squares with only 30 black squares and still 32 white squares.

We have to cover every white square, so we need at least 32 dominoes. But there are 32 dominoes that have to cover 30 black squares. So by the Pigeonhole Principle, at least one black square is covered by two dominoes. But this means there would be an overlap! So we can’t cover the chessboard like this.

-

-

If 95 people are seated in a row of 100 chairs, then show that some consecutive set of 16 chairs are filled with people.

We have \(100-95=5\) empty chairs that split up the row into \(n=6\) contiguous blocks of filled chairs. But with \(k=15\), we see that \(6 \cdot 15 = 90 < 95\), so at least one block of chairs has \(16 = k+1\) people sitting in a row by the Generalized Pigeonhole Principle.

-

If 95 people are seated in a circle of 100 chairs, show that some consecutive set of 19 chairs are filled with people.

We have \(100-95=5\) empty chairs that split up the row into \(n=5\) contiguous blocks of filled chairs (the difference from part (a) here is sneaky; it has to do with how the chairs are now lined in a circle!). But with \(k=18\), we see that \(5 \cdot 18 = 90 < 95\), so at least one block of chairs has \(19 = k+1\) people sitting in a row by the Generalized Pigeonhole Principle.

-